The Hirsel is proud to be the home of Highland Wool, a Community Interest Company (CIC) formed in 2022 in order to support a sustainable wool industry in Scotland. You can find out all about them here: www.highlandwool.scot.

The following is adapted from a talk presented at the 10th anniversary edition of the Scottish Yarn Festival, 30 August 2025

This is a batt, wool from a sheep – in this case, one of our Hebrideans – that has been washed and carded ready for onward crafting. You can find a batt to suit your project in many places: at your local market or farm shop, at craft stores, online. You may make them yourselves. There’s nothing special about it. Except everything.

The wool in this batt was grown and shorn on our farm in the Highlands, and processed into this batt in a mill in the Highlands – it’s 100% Scottish, and 100% Highlands. Whatever it becomes next – a felted critter [pic], spun yarn, or a peg loom rug – this batt and others like are special because they’re being made in the only consignment mill – a mill that takes your fleece, processes it, and gives it back to you to do with what you will – the only consignment mill in the Highlands, and only one of two in mainland Scotland at the moment. There are more mills in Scotland, and in the UK, of course. And on the islands – the islands are actually ahead of the mainland on this issue. Part of Highland Wool’s mission is to address the scarcity of consignment mills on the Scottish mainland.

This batt didn’t come into being overnight – you could say it’s taken almost 60 years to make.

The Gillies family bought the farm now known as The Hirsel [2] – a few acres of rough grazing, woodland, bog, and a bit of arable land – in 1969 with high hopes. But during most of the 50 years after that, it was a wearying money pit, and both sons went to work in their early teens to contribute to the family finances. After their father died, their mum let the cows go, but kept her hand in with sheep

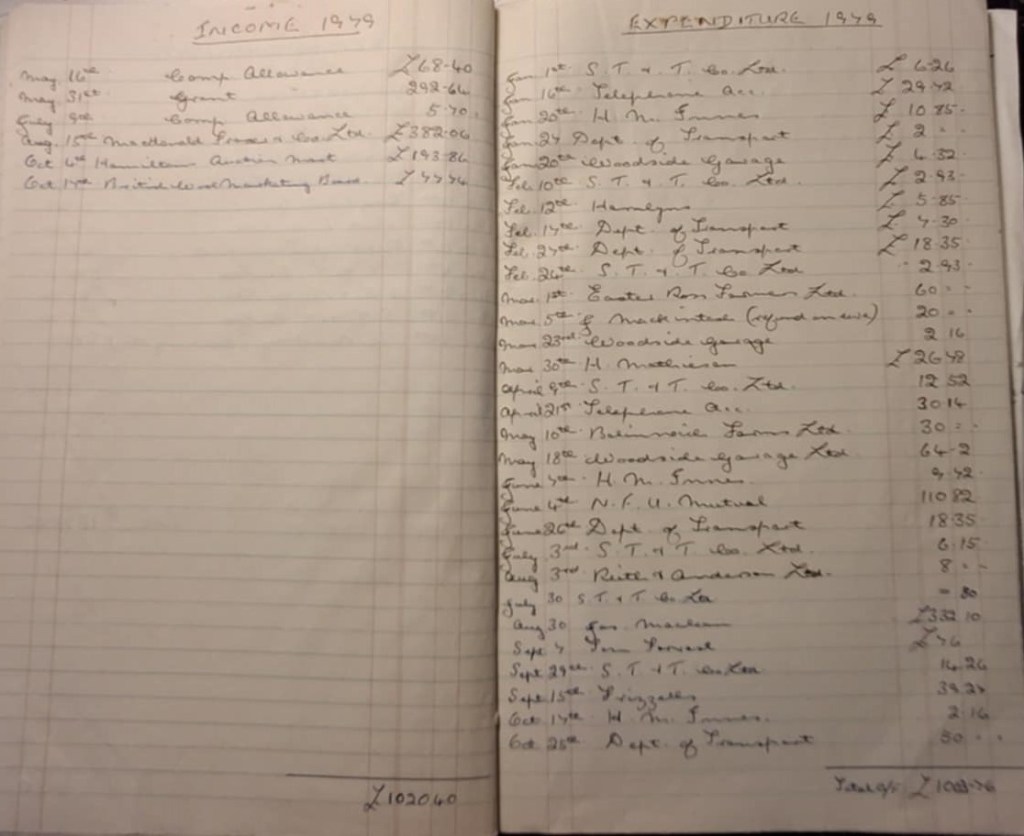

– until the late 70’s when she retired. Both sons were away earning their own livings by then, and neither wanted to be a farmer. She looked at her pension, did the math, and sold the sheep.

She tried renting the fields to other farmers, but became afraid their tenant rights would lead to her losing the land, so she stopped all farming activity. Throughout the farm’s more than 200+ years, it has repeatedly gone through these cycles of being worked, then being abandoned . Fields that had supplied potatoes to the local school and grazing for the sheep grew boggy, gorse and brambles spread at the edge of the woodlands, the grass grew tall and manky, and the birch grew thick.

The land nesting critters and small birds moved out, and without critters and birds to feed on, larger critters moved out too. Without the sheep spreading their manure, the soil turned poor, as it is naturally in the Highlands. The fences fell down, and the barns and sheds fell to bits. Neglect did allow some good to happen: any chemicals the family had used got washed out of the land, the ditch meandered and returned to the burn it was originally. And the farm missed out on the ‘modernization’ and moves toward ‘efficiency’ that had woodlands and hedges disappearing on other farms all over the UK.

Mum held onto the farm through this period of neglect in hopes that when she passed, the boys would have something they could sell. This was her legacy, the only way she could think of the farm finally earning anything for the family: to sell it.

This was the state of the farm when she took a fall and started needing care. Her eldest son Donald, who was home temporarily at the time, stayed to help care for her.

Now a consultant in the construction industry, Donald settled into and began working from a caravan across the yard from her house. Sitting at his desk, looking out the window at the boggy fields and broken-down fences…he caught the fix-it bug, and bought a tractor, a digger and some other gear. He got into farming because he likes working with machinery.

I got into farming because I like Donald.

I’d always been a country girl, running wild with my siblings and cousins through the desert and mountains of my childhood, and getting out into the country as much as possible while chasing a career through the big cities as an adult. By the time Donald and I met, I was ready for a career change, and to re-embrace a more rural life again.

I joined him on the farm in 2015, we harvested our first hay that summer, brought sheep onto the farm in the autumn, and stumbled through the Hirsel’s first lambing in 35 years the following spring. So now we were farmers… of a sort.

Being the optimists we are, we decided we could break the cycle, we could make the farm a success. We vowed to do all we could to keep it from being abandoned again – or being bulldozed for holiday homes or timber – once we were too old to work it. But that meant we had to go about things differently than Donald’s family had before. We had to try to make choices that would be financially and environmentally sustainable into a future beyond us. This farm had to become something that our successors would want to work, that could support itself and the family who might live on it.

Our choices started reflecting that. Our first act was to not choose for the NC Cheviots his family had kept when he was a boy: we chose Hebrideans, and choosing them changed everything.

Hebrideans are great for a lot of reasons: they’re native to Scotland, they survive on anything green, and are able to live outside all year round, which was important because our farm buildings are unfit to house livestock anymore. They don’t bring as much as other breeds at the market, but don’t cost as much to keep, they’re smart and trainable, and good for the soil and the plant life on the farm, because they won’t overgraze unless they have too, and they fertilize everywhere. They’re super protective of their young, so we’ve only lost a few lambs as the farm became more welcoming to predators again. We picked them deliberately, for these reasons, and they taught us how to start thinking about our farming life in a holistic way: how do our choices affect our lives and the future of the farm, not just for the next harvest, but the next generation. These questions have shaped our approach to farming and to making the farm environmentally and financially sustainable ever since. Later, when we started considering diversification ideas, this holistic view would shape our choices there, too.

Meanwhile, we got busy with our sheep.

We love our sheep…but when we started shearing them in 2016, we learned how very little their wool was worth. With the dive in wool prices these past few years, most farmers are in this boat with us now, but it was quite a shock to us at the time.

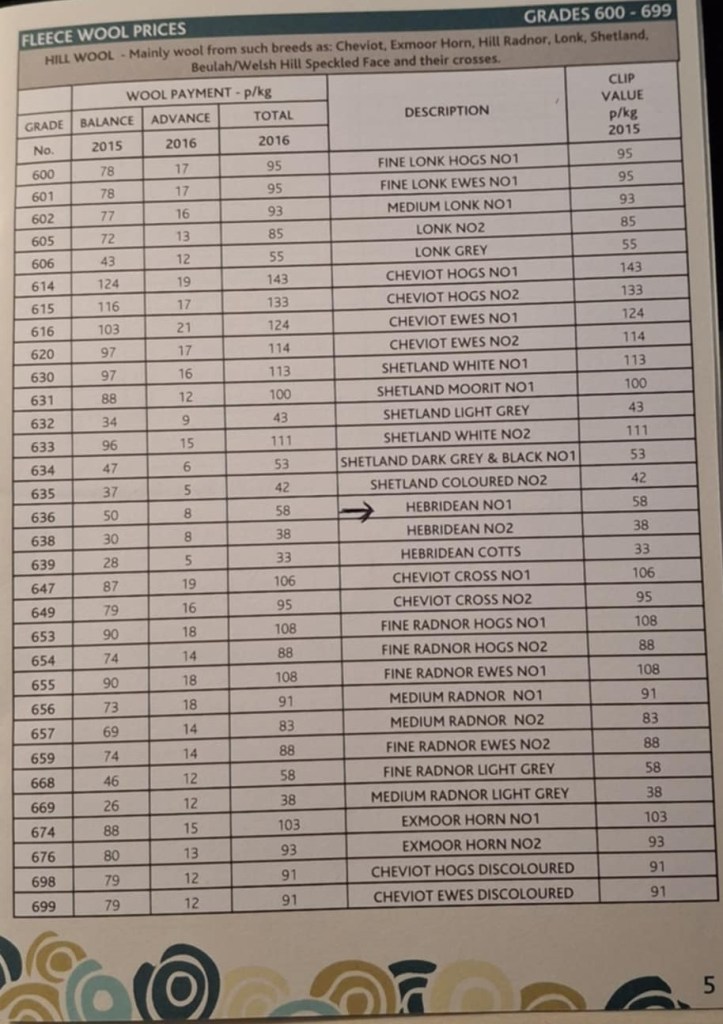

In 2016 the wool board would’ve paid us, at best, 58p/kg. It rose to 62p the next year. In 2024, it dropped back to 46p. All these prices are higher than the ones that had made mum give up sheep.

But I learned that wool from heritage breed sheep wasn’t required to be sent to the board, and any breed was exempted if I processed the wool myself, or sold it to someone who was going to use it themselves. Now, the board works for some of you, and if it does, that’s great. I’m never going to rag on the Wool Board, as some farmers do, I’m a fan of its stated goals, and the cooperative model it was founded on. But given our circumstances, I turned away from the board, and starting looking for other options.

We needed to earn an income from our wool, not just use it in the garden and to repair farm tracks – although those are some of the great uses we still put it to. But we needed to create a saleable product from it as well, for it to become part of the patchwork of income streams for the farm, if our sheep were going to keep from becoming just an expensive hobby – or a repeat of the reasons mum gave them up. So: yarn?

Hebridean wool used to be prized for outer wear and rugs. But it would have been a big chunk of our budget, in those early days, to have it turned into yarn – £36.50/kg plus vat in 2016, and the mill I inquired at had a 30kg minimum at the time. It would have taken me two years to harvest that much decent fleece from our small flock – and if you have a lanolin heavy breed, like Hebrideans, you know what being stored for a year does to unwashed fleece. And – call me crazy – I wanted our Scottish fleece processed locally, in Scotland. A lot of farmers and makers will recognize this story, It was all rather depressing.

So I started teaching myself how to process our wool at home on the farm. Washing outdoors in the old horse trough and in buckets to preserve our pipes, and drying on old clothes racks, learning to needle felt or make felted rugs, I was joining a community of self-processors across the nation – the world, actually. But like so many others, I was at the mercy of my free time between farm chores, the Scottish weather because I didn’t have a proper workshop, and my skills – or lack of them. It was a long slow learning curve. I did, however, find that I liked washing fleece very much.

At the same time, we were starting to get on top of the fencing and field work…and started having time to think about the future of our dilapidated farm buildings

The farm is old, it’s already visible on the earliest maps we have of the area, and so are its buildings – and they show it. The steading is a mish-mash of old stone barns, a couple of caravans, a big metal shed, a wooden garage, historic middens, and lately a couple of portacabins.

At that same time, we and other farmers were being told ad nauseum that we had to ‘diversify’ to make our farms financially sustainable. You couldn’t just feed people anymore, if ever that was possible. Being located in a high tourism area, our choices seemed to be to become a campground or a visitors’ attraction… I rather felt like I was back in my previous career, waiting tables so I could afford to be a theatremaker. But we tried. We tried camping –and it wasn’t a good fit: having to be nice to people before 10am is a tough one for both of us – just ask the Highland Wool team. The camping experiment, though, reminded us of an important rule: if our diversification attempts were to succeed, we needed to find a project that fit – our personalities and skills, the size and character of the farm, the water and power issues – we’re on our own water supply – and the reuse-everything-waste-nothing-that-might-have-a-second-or-third-use character of our farming style.

So my liking for washing wool helped us to start thinking of repairing one of the buildings and putting a mill in it… Highland Wool is now resident in three of our outbuildings – a wooden shed, a portacabin, and the caravan Donald lived in when he first moved back to the farm.

Researching the project, I discovered all the reasons there are so few mills in a country known for having more sheep than people – the major one being that the industrial revolution sucked all the fibre processing south, decimating what was once a thriving cottage industry, before the industrial boom went nearly bust. I learned about power and water and mill waste. I looked into a couple of failed mills near us, and why they failed. I talked and emailed with others who’d considered the idea and backed away from it – water issues were a big reason for some. And then we dragged our feet for a few years about starting what had become a big scary project…

Until 2021, when the conversation broadened out to include some like-minded farmers, crofters, and crafters Donald met at a workshop. He mentioned that we were discussing this…emails started zinging back and forth, and after 5 years, the project stopped being about whether we would start a mill and became about the team that would. In February 2022, Highland Wool was formed as a community interest company to ‘support a sustainable wool industry in Scotland’.

Community, wool, sustainability, and Scotland being central to our values. And infrastructure being our first challenge.

As I mentioned above, at this time there are only two consignment mills in mainland Scotland. The Border mill is one of them. 270 miles, 5 ½ hours south of the farm, and with a waiting list. Highland Wool, still in its infancy, is now the other one. This isn’t a brag, being one of only two: it’s a problem. The Scottish government’s 2024 Agricultural census tells us that there were almost 6 and a half million sheep in Scotland, the Journal of Scottish Yarn’s excellent map shows over 60 “fleece to fibre” businesses in Scotland. The Highlands – and Scotland – has a thriving craft community …and we have only 2 consignment mills on the mainland. Two. For the most part, wool from mainland Scotland and some of the islands is being sent to England and beyond to be processed, before being sold on or coming home again. That’s just wrong. The team at Highland Wool hope to be a small part of changing that.

We started with a lot of discussion about who we would be, what we would offer people, and which people we would offer it to. We decided we’d take small orders, 1 fleece to 25kg, to serve small breeders who were unable to meet the minimum weights at the other UK mills – or large commercial shepherds who had a small fibre flock on the side. We’d serve fibre makers who bought or were given fleeces direct from the farmer, who didn’t want to get mucky – or ruin their sinks washing their fleeces. Or who were trying to ‘keep it Scottish’, as one maker recently said. We’d keep to the Highlands and Islands to limit the miles we’d be putting on the wool, and the travel for our customers. We’d just take the wool to batts, as spinning would need more space and skills – and money to get started. And I think a batt is wool at its most ‘potential’, able to be taken in any direction by the makers who will be using it. We’d be low energy, no waste, and recycle our water – necessity being the mother of invention, as the farm is on its own water supply, and the water and power has to be shared with the house and farm for the moment. Also, our area gets power outages that take days to repair, the world is getting pandemics that break supply chains, and you know, the fall of civilization might be eminent… and we need to keep working through it all. Any time a new process is introduced, we would ask ourselves: does it have to be plugged in? Do we need it? Or is it just as good – maybe better – being done by hand? We would be a bit primitive, which we don’t see as a pejorative, but an advantage. Now, more than three years from our founding, Highland Wool isn’t far off from those goals. And an unexpected plus was the social side of working with our hands, and each other.

At the same time, I was trying to figure out how much money we’d need to buy the equipment for the mill. And where we’d find the equipment. It’s not like other tools and machinery – you can’t just get on over to the warehouse and pick out some carding machines – they’re just not being made in the UK anymore. Equipment is still being made overseas, but tends to be large, and post Brexit, anywhere outside of the UK was going to be a nightmare mix of customs, shipping, and international travel for us, while we needed to stay close to our farms and businesses. We thought – with all the mills that have closed down – there must be some old equipment floating around the UK somewhere… But the company I found trading in used equipment tends to have the large machines… and then one of our supporters told us about a farmer down in Oban with a small collection of stuff sitting in his barn. We sent Donald down to look at it, and found the S. Walker & Sons Victorian carder now affectionately known as Caroline [16].

The farmer was selling his entire collection for £5000, and with a deposit, he’d hold it for us while we raised the money. We started a crowdfunding campaign and had 136 generous donors, and loans from a supporter in Wales and from Donald, made the purchase…and in September 2023, equipment started arriving on the farm.

We got to work learning how to open fleece (by hand), wash (also by hand), and to pick and card using our new to us Belfast picker and an e-carder

Then via social media, we found a farmer in Nairn who was looking to offload nearly 300 Shetland fleeces. She gave the fibre community a couple of days to take what they wanted and then it was all going to landfill. Unless someone committed to taking it all, then they’d hold it a little longer. I committed. Actually, I committed Donald – he drove our sheep trailer out, and picked it up. I don’t think I realized just how much wool that many fleeces really would be. We learned our process on this, and on about 3 years of Hebridean back log from our farm.

That fleece was the first we sold in 2024, and that and the Hebridean were the first to go through Caroline this year, when it was time to start test runs. We’re still using it in workshops, along with the better product we’re able to make now. It was a lot of fleece for our micro-mill to take on all at once. We won’t be doing that again!

Then, in the summer of last year, we starting selling a bit, and thought we were ready to take on our first clients. But it took months to card 25 kg of our customer’s wool on the e-carder we were using while Caroline was being repaired, and we were all volunteers with other work, so we couldn’t be at the mill every day. We were never going to be financially viable that way. We’re extremely grateful to those first few clients, for their patience and support.

Finally, we were awarded a grant which included funds to repair Caroline. We thought we had completed repairs in February of this year, but she broke down again about 4 hours after we got her started. The carding fabric on one of the rollers looked alright, but basically crumbled to bits, shedding metal tines, once we started rolling. It took weeks to source replacement fabric – from Italy. But we got her back together, vacuumed all the tiny spikes out of her and off the floor, ran some more tests with the Shetland and Hebridean, and in August 2025 we were finally able to risk putting through some lovely Black Cheviot we bought from our neighbour. [20] We’re putting the Hirsel’s 2025 harvest of Hebridean wool through at the time of writing, 9 years after Donald and I sheared our first sheep and asked: what are we going to do with all this wool.

This year will be the year that will prove whether the mill can make it or not. I know we won’t earn enough to be financially viable this year, we’re still heavily reliant on grant monies, but some of that has funded turning two of our volunteers into employees, with new volunteers stepping in to help. But as they step up to regular hours, as we use Caroline to turn more orders out faster, and finally finish the water recycling system and fix the electrics… we will see if it all functions together. Then next year, we’ll see if it functions and can earn it’s keep. If it can become part of the mosaic of sustainability we’re building for our farm’s future, and for the future of our farming and fibre community. To see if it helps build the dream so many of us share of a thriving Scottish fibre industry.

So. That’s the story of how a batt was made, and how it and Highland Wool is helping our farm – and one day other farms – build a sustainable future.